The Printed Hibiscus

Artist notes / short excerpt from catalogue...

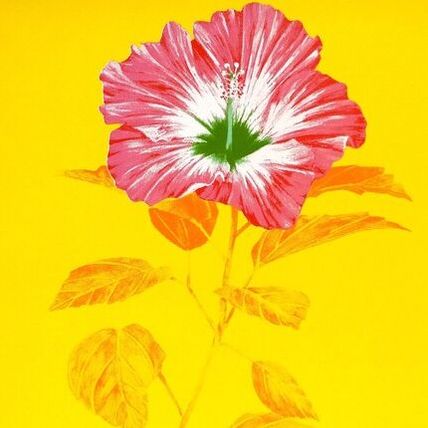

The Printed Hibiscus is an exploration into botanical study and floral fabric history, settling uncomfortably on the stylised hibiscus as it has come to represent / misrepresent the South Pacific. The project research became surprisingly convoluted, taking several unexpected turns. I began with the flower as a botanical specimen, connecting to its global plant genus, exploring the intersection between humans and plants as an ethnobotanical subject, and finally through my own personal and process based experience. A photograph of my Grandparents in Honolulu in the 1990’s sent me into a rabbit hole of research around Hawaiian shirt history and design leading to a desire to not only note that history, but to reference it directly in my work.

The hibiscus motif itself is not discussed through its cultural use by indigenous Pacific communities but instead, references the flower as a brand through fabric design history, centred on its nearly 100 year old connection to Hawai’i. The focus is narrowed to the printed hibiscus image that is recognised around the world through the infamous ‘Hawaiian’ or ‘Aloha’ shirt. The origins of the shirt and design are traced to Japanese and Chinese “craftsmen, who made kimonos and shirts of fabrics imported from their homelands.”

In an ethnobotanical sense, flora and fauna have been used to connect places and people for centuries. The common red hibiscus Hibiscus rosa-sinensis (literally translating from Latin to Rose of China) is the National flower of Malaysia and in South China is a symbol of happiness and prosperity. But its associative repetition in the South Pacific, onto brightly printed fabrics, means something else, especially when that branding was largely targeted to American servicemen and tourists flooding into the newly annexed state of Hawai’i with minimal consultation or input from the indigenous communities.

Relative to this moment in time, I consider the possibility that these motifs repeated, over and over, may become simplified and meaningless, or as Andy Warhol commented on his repeated series, “the more you look at the same exact thing…the better and emptier you feel.” But on the other hand, meaning and meaninglessness, becomes relative to context. For example, living or visiting an island such as Rarotonga places the tropical floral print into the very environment that inspired it.

Necessarily, the ‘Hawaiian’ floral shirt design has evolved and been reclaimed by many talented indigenous designers, intent on overriding the dominance of global manufacture with a significantly more authentic cultural resonance and production. In the last two decades particularly, ‘Pacific branded’ fabrics have been made by indigenous Hawaiians, in a similar way to Rarotongan craftspeople selling hand dyed and printed pareu with designers such as Elena Tavioni in the Cook Islands whose TAV fashion label sells garments branded with Cook Islands motifs.

Those of us who have visited or lived in any South Pacific Island most likely have worn a Hawaiian style shirt, sarong or dress. We have seen celebrities from Elvis in the early 1960’s to Leonardo De Caprio and Johnny Depp branding contemporary and retro designs bringing the style into the mainstream, and out of a specifically Pacific island context. It’s been suggested that there is a rebellious freedom that comes from wearing bright botanical patterned shirts especially when contrasted with the crisp business shirt and tie of the West. Dale Hope, author of a comprehensive book on the subject, notes that the very first shirts made from Japanese kimono fabric of this style were worn by American service-men in Hawai’i to show they were ‘off duty’. In my own family, once retired, my Grandfather had a collection of Hawaiian shirts that he wore mainly during his time in Oahu which also signified a similar state of being...

The Printed Hibiscus is an exploration into botanical study and floral fabric history, settling uncomfortably on the stylised hibiscus as it has come to represent / misrepresent the South Pacific. The project research became surprisingly convoluted, taking several unexpected turns. I began with the flower as a botanical specimen, connecting to its global plant genus, exploring the intersection between humans and plants as an ethnobotanical subject, and finally through my own personal and process based experience. A photograph of my Grandparents in Honolulu in the 1990’s sent me into a rabbit hole of research around Hawaiian shirt history and design leading to a desire to not only note that history, but to reference it directly in my work.

The hibiscus motif itself is not discussed through its cultural use by indigenous Pacific communities but instead, references the flower as a brand through fabric design history, centred on its nearly 100 year old connection to Hawai’i. The focus is narrowed to the printed hibiscus image that is recognised around the world through the infamous ‘Hawaiian’ or ‘Aloha’ shirt. The origins of the shirt and design are traced to Japanese and Chinese “craftsmen, who made kimonos and shirts of fabrics imported from their homelands.”

In an ethnobotanical sense, flora and fauna have been used to connect places and people for centuries. The common red hibiscus Hibiscus rosa-sinensis (literally translating from Latin to Rose of China) is the National flower of Malaysia and in South China is a symbol of happiness and prosperity. But its associative repetition in the South Pacific, onto brightly printed fabrics, means something else, especially when that branding was largely targeted to American servicemen and tourists flooding into the newly annexed state of Hawai’i with minimal consultation or input from the indigenous communities.

Relative to this moment in time, I consider the possibility that these motifs repeated, over and over, may become simplified and meaningless, or as Andy Warhol commented on his repeated series, “the more you look at the same exact thing…the better and emptier you feel.” But on the other hand, meaning and meaninglessness, becomes relative to context. For example, living or visiting an island such as Rarotonga places the tropical floral print into the very environment that inspired it.

Necessarily, the ‘Hawaiian’ floral shirt design has evolved and been reclaimed by many talented indigenous designers, intent on overriding the dominance of global manufacture with a significantly more authentic cultural resonance and production. In the last two decades particularly, ‘Pacific branded’ fabrics have been made by indigenous Hawaiians, in a similar way to Rarotongan craftspeople selling hand dyed and printed pareu with designers such as Elena Tavioni in the Cook Islands whose TAV fashion label sells garments branded with Cook Islands motifs.

Those of us who have visited or lived in any South Pacific Island most likely have worn a Hawaiian style shirt, sarong or dress. We have seen celebrities from Elvis in the early 1960’s to Leonardo De Caprio and Johnny Depp branding contemporary and retro designs bringing the style into the mainstream, and out of a specifically Pacific island context. It’s been suggested that there is a rebellious freedom that comes from wearing bright botanical patterned shirts especially when contrasted with the crisp business shirt and tie of the West. Dale Hope, author of a comprehensive book on the subject, notes that the very first shirts made from Japanese kimono fabric of this style were worn by American service-men in Hawai’i to show they were ‘off duty’. In my own family, once retired, my Grandfather had a collection of Hawaiian shirts that he wore mainly during his time in Oahu which also signified a similar state of being...

Above: detail of Yellow / Heaven, screen print from original painting; Printed at ScreenCulture New Plymouth/ NZ.

Left: Eternity (fabric installation artwork from orginal Hibiscus Tyger tyger, fabric layup Mark Evans) centre: Stolen, watercolour on paper. Right: Fallen, watercolour on paper. Below left: Hibiscus Tyger tyger, work-in-progress watercolour on bamboo paper. Centre:Fearful Symmetry LED light, Right: CU Hibiscus Tyger tyger Coral fabric. 2023 T.Forbes©

Left: Eternity (fabric installation artwork from orginal Hibiscus Tyger tyger, fabric layup Mark Evans) centre: Stolen, watercolour on paper. Right: Fallen, watercolour on paper. Below left: Hibiscus Tyger tyger, work-in-progress watercolour on bamboo paper. Centre:Fearful Symmetry LED light, Right: CU Hibiscus Tyger tyger Coral fabric. 2023 T.Forbes©

Home Work Taranaki: Puke Ariki Museum

22 September 2020 - 8 February 2021

Artwork: All Good / NZ Giant Kelp (a response to marine temperature fluctuation & local extinction) (2020). Medium: LED light and acrylic on plastic/cloth bubble wrap.

PRESS

Who/what inspired you to become an artist?

I have never felt like I had a choice to be an artist or not, so I can't honestly say I was inspired to be an artist. That said, I have devoted a considerable amount of my life to the study of art and artists and the predominating thought is this: art plays a vital role in our lives by allowing us to shift the view on its subject. It may be enough just to create or represent something beautiful or it may be a deeper more conscious act of provoking the viewer into a different thought - even if just briefly. As Malcolm Miles puts it in his book on Eco-aesthetics (2014), "Art cannot save the planet or a whale; it can represent, critique and play imaginatively on the problem."

What would you like our audience to take away/ learn from looking at your artwork?

This is the first in a series of works that are an active exploration of the value of connection to land/home/history contrasted with the weird psychology of human denial that sits alongside the environmental polemic.

The light work All Good is accompanied by a small botanical painting of giant NZ kelp painted directly onto the plastic packaging that came with the light. The subject is inspired by a significant amount of dead kelp and plastic recently washed onto my local beach. Contemplating the importance of New Zealand's giant kelp forests to marine ecology this work signposts the threat of single species loss to a greater ecosystem on which we (and innumerable other species) are dependant.

“All good” has become an easy way of avoiding confrontation, often meaning it will be fine, it’ll all work out. In the context of this project, it's intention is unapologetically ironic.

YOU TUBE :Inside the Artist's Studio (virtual tour)

Who/what inspired you to become an artist?

I have never felt like I had a choice to be an artist or not, so I can't honestly say I was inspired to be an artist. That said, I have devoted a considerable amount of my life to the study of art and artists and the predominating thought is this: art plays a vital role in our lives by allowing us to shift the view on its subject. It may be enough just to create or represent something beautiful or it may be a deeper more conscious act of provoking the viewer into a different thought - even if just briefly. As Malcolm Miles puts it in his book on Eco-aesthetics (2014), "Art cannot save the planet or a whale; it can represent, critique and play imaginatively on the problem."

What would you like our audience to take away/ learn from looking at your artwork?

This is the first in a series of works that are an active exploration of the value of connection to land/home/history contrasted with the weird psychology of human denial that sits alongside the environmental polemic.

The light work All Good is accompanied by a small botanical painting of giant NZ kelp painted directly onto the plastic packaging that came with the light. The subject is inspired by a significant amount of dead kelp and plastic recently washed onto my local beach. Contemplating the importance of New Zealand's giant kelp forests to marine ecology this work signposts the threat of single species loss to a greater ecosystem on which we (and innumerable other species) are dependant.

“All good” has become an easy way of avoiding confrontation, often meaning it will be fine, it’ll all work out. In the context of this project, it's intention is unapologetically ironic.

YOU TUBE :Inside the Artist's Studio (virtual tour)

In another light: Part II

Muse Gallery, Havelock North, 30 August 2020

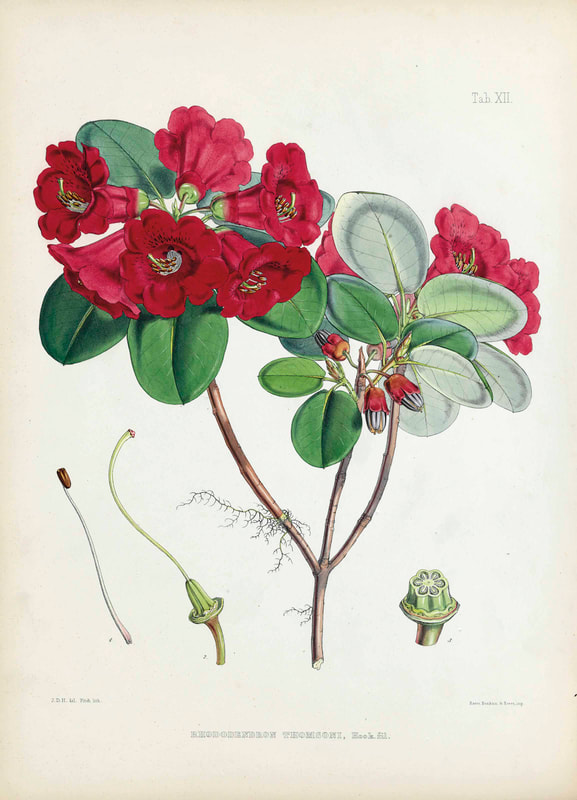

Left: T.Forbes: Facsimile No I, Rhododendron Glaucum From Hooker & Fitches Sikkim-Himalaya collection 1851- 2020, August 2020

Right: Print from Hookers Rhododendrons of Sikkim- Himalaya 1851.

Right: Print from Hookers Rhododendrons of Sikkim- Himalaya 1851.

Part two of an exhibition first shown in New Plymouth, Taranaki in 2018, this exhibition will include a print series from the original works made up at Pukeiti Gardens, a light work from the same show and two new original paintings based on Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker's Rhododendrons of Sikkim-Himalaya's from the mid 1880's.

"Still fascinated with the early processes of C19th botanical art and collection, that included detailed colour studies and sketches, the new works focus on original study notes and the idea of facsimile. These are taken directly from two works made by Hooker and finished by Walter Hood Fitch. There is a conscious absence of flowers in the works shifting the focus instead to the foliage body of the plant and the purity of the flower as saturated colour, redirected into the plants background."

"Still fascinated with the early processes of C19th botanical art and collection, that included detailed colour studies and sketches, the new works focus on original study notes and the idea of facsimile. These are taken directly from two works made by Hooker and finished by Walter Hood Fitch. There is a conscious absence of flowers in the works shifting the focus instead to the foliage body of the plant and the purity of the flower as saturated colour, redirected into the plants background."

Work in progress, August 2020.

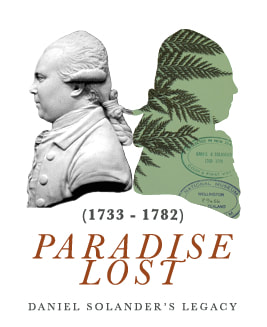

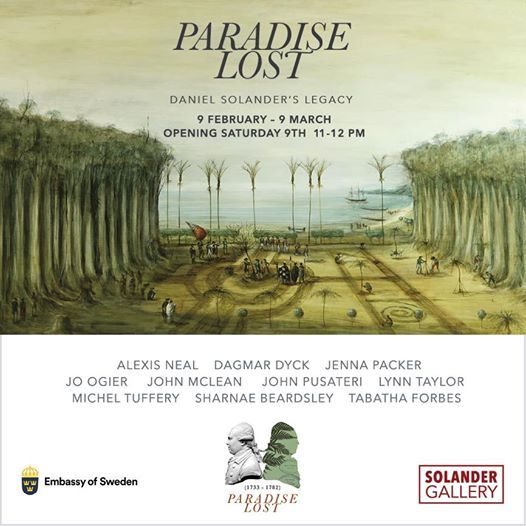

Paradise Lost:

Daniel Solander's Legacy

Group Exhibition, Solander Gallery Wellington 2019 - 2020

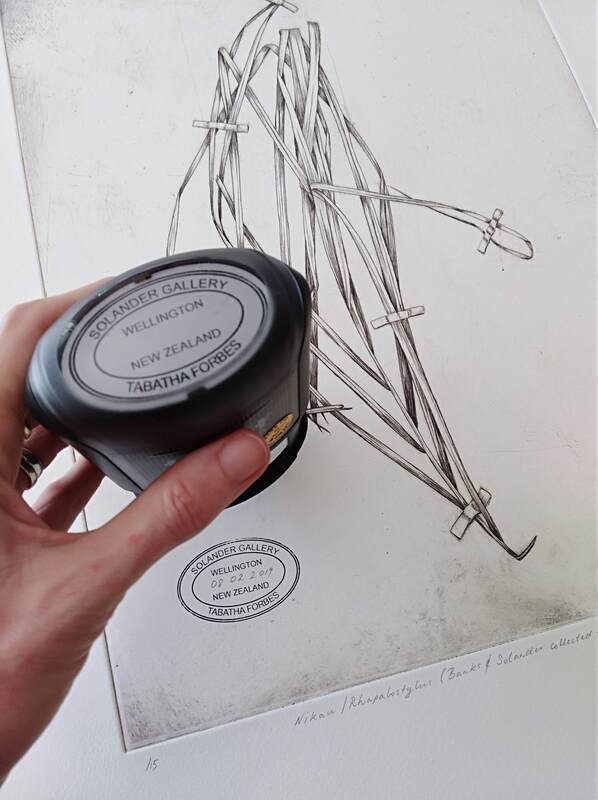

Painted from a grass specimen originally collected by Daniel Solander from Aotearoa NZ, 1769. Acrylic house paint on paper. T.Forbes©

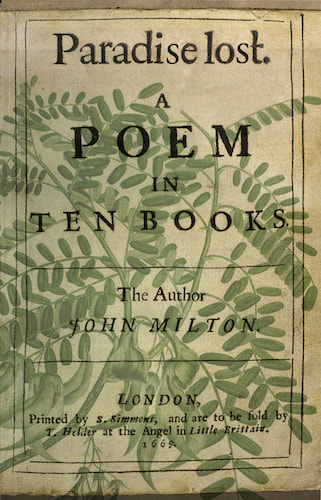

Images: Solander exhibition logo, John Milton's Paradise Lost, Original painting T.Forbes© included in Wellington show, cover of exhibition catalogue.

The following text on the project is from Solander Gallery website as linked here: solandergallery.co.nz/exhibition/paradise-lost-daniel-solanders-legacy/

To coincide with the 250th Anniversary of Cook’s first voyage to the Pacific, Solander Gallery and project partner Embassy of Sweden in Canberra will open Paradise Lost, a group exhibition to commemorate the contribution naturalist Daniel Solander made to New Zealand’s history.

The ten artists selected each bring a unique vision to this historical event and collectively put flesh to many of Daniel Solander’s facets, not least of which are his scientific credentials in botany, his cross-cultural awareness and his enthusiasm for the preservation of the unique species of the natural world.

Participating artists are, John Pusateri (Auckland), Alexis Neal (Auckland) Dagmar Dyck (Auckland), John McLean (New Plymouth), Tabatha Forbes (New Plymouth), Michel Tuffery (Wellington), Sharnae Beardsley (Christchurch), Jo Ogier (Christchurch), Lynn Taylor (Dunedin) and Jenna Packer (Dunedin).

Scientist Joseph Banks, employed Daniel Solander, a Swedish botanist and together they collected hundreds of plant species as the Endeavour circumnavigated New Zealand 1769.

As paper was in short supply in 1760’s England, Banks and Solander bought printers proof of Milton’s book Paradise Lost and it was pages from this work that were used to press and dry the first European collections of New Zealand plants.

A 35 page colour catalogue Paradise Lost – Daniel Solander’s Legacy is also available online or from Solander Gallery.

Touring Dates:

Russell Museum | Te Whare Taonga o Kororareka | 5 April – 18 May 2019

Dargaville Museum | Te Whare Taonga o Tunatahi | 2 June – 7 July 2019

Reyburn House Art Gallery, Whangarei | 16 July – 18 August 2019

Auckland Botanic Gardens, Manurewa | 2 September – 11 October 2019

The University of Auckland | Old Government House |17 October – 15 November 2019

Puke Ariki | New Plymouth | 25 November – 17 January 2020

Millennium Public Art Gallery, Blenheim | 14 March – 26 April 2020

To coincide with the 250th Anniversary of Cook’s first voyage to the Pacific, Solander Gallery and project partner Embassy of Sweden in Canberra will open Paradise Lost, a group exhibition to commemorate the contribution naturalist Daniel Solander made to New Zealand’s history.

The ten artists selected each bring a unique vision to this historical event and collectively put flesh to many of Daniel Solander’s facets, not least of which are his scientific credentials in botany, his cross-cultural awareness and his enthusiasm for the preservation of the unique species of the natural world.

Participating artists are, John Pusateri (Auckland), Alexis Neal (Auckland) Dagmar Dyck (Auckland), John McLean (New Plymouth), Tabatha Forbes (New Plymouth), Michel Tuffery (Wellington), Sharnae Beardsley (Christchurch), Jo Ogier (Christchurch), Lynn Taylor (Dunedin) and Jenna Packer (Dunedin).

Scientist Joseph Banks, employed Daniel Solander, a Swedish botanist and together they collected hundreds of plant species as the Endeavour circumnavigated New Zealand 1769.

As paper was in short supply in 1760’s England, Banks and Solander bought printers proof of Milton’s book Paradise Lost and it was pages from this work that were used to press and dry the first European collections of New Zealand plants.

A 35 page colour catalogue Paradise Lost – Daniel Solander’s Legacy is also available online or from Solander Gallery.

Touring Dates:

Russell Museum | Te Whare Taonga o Kororareka | 5 April – 18 May 2019

Dargaville Museum | Te Whare Taonga o Tunatahi | 2 June – 7 July 2019

Reyburn House Art Gallery, Whangarei | 16 July – 18 August 2019

Auckland Botanic Gardens, Manurewa | 2 September – 11 October 2019

The University of Auckland | Old Government House |17 October – 15 November 2019

Puke Ariki | New Plymouth | 25 November – 17 January 2020

Millennium Public Art Gallery, Blenheim | 14 March – 26 April 2020

Image: This is from the drypoint prints (hand printed by Michaela Stoneman) that I made directly from my original painting (based on a nikau specimen collected by Solander & Banks 1769-71 NZ) T.Forbes©

In Another Light: Rhododendron Project (Part I & II) 2018

Part I: Kina Design & Artspace, 101 Devon St, New Plymouthrt I:

26 October – 20 November 2018

Part II: Pukeiti Rhododendron Gardens, The Lodge, 2290 Carrington Rd, New Plymouth

2 November – 16 November 2018

Additional events during Taranaki Garden Festival: www.gardenfestnz.co.nz/

Painting in Residence, Pukeiti Lodge

31 Oct – 1 November (10am – 5pm)

Botanical Art Workshops 2018, Pukeiti Lodge:

11 - 12 August: Adults beginners botanical workshop

6-7 October: Kids botanical workshop

3 – 4 November: Adults botanical art workshop

Part I: Kina Design & Artspace, 101 Devon St, New Plymouthrt I:

26 October – 20 November 2018

Part II: Pukeiti Rhododendron Gardens, The Lodge, 2290 Carrington Rd, New Plymouth

2 November – 16 November 2018

Additional events during Taranaki Garden Festival: www.gardenfestnz.co.nz/

Painting in Residence, Pukeiti Lodge

31 Oct – 1 November (10am – 5pm)

Botanical Art Workshops 2018, Pukeiti Lodge:

11 - 12 August: Adults beginners botanical workshop

6-7 October: Kids botanical workshop

3 – 4 November: Adults botanical art workshop

Images: Tabatha Forbes © Top image: Yellow Rhodo Lightwork (Acrylic UV print and LED neon flex light). Works below, study and installation pictures.

To see more visuals as this project progresses, please clink on insta- link below:

To see more visuals as this project progresses, please clink on insta- link below:

About the project:

"For nearly two decades my work has been increasingly concerned with the link between early C18th European perceptions of the South Pacific through collection and documentation and present day manifestations of those aesthetics and agendas. For example, how we value nature (flora & fauna) and how that evolves and recedes through the current influence of economy, beauty, politics and ecology.

The story of how nature is initially seen (both in indigenous and European histories) and how it is developed as a 'productive' resource, is always a curious story to tell. Drawn to Pukeiti Rhododendron Gardens, for its inception as a sanctuary, I was particularly inspired by an opening passage in Graeme Smiths Pukeiti book (1997),

“At first glance, the killing fields of Gallipoli and the Somme would appear to have nothing in common with Pukeiti. In a paradox of history, however, one gave birth to the other...

After two world wars and the decimation of many parts of the old World, and not a few areas of

New Zealand, there seemed to be a general coming together of people interested in plants. The ravages of war and its lost generations, combined with the blackened stumps of a blighted local landscape, cleared for pasture, made some people aware of what was being destroyed. Tree, flowers and birds, amongst other things, ‘restoreth the soul’” p 10.

I imagined some of the Pukeiti founders, such as Douglas Cooke who served in Egypt, Gallipoli and France during World War I, returning to New Zealand with the dream of creating a place of natural tranquility and beauty, contrasting completely the devastation of both humanity and landscape experienced through war.

Within the research for this project I have also drawn on some of the C19th plant-hunting stories and the visual representations of those early collections. I was fortunate to see a copy of the precious Joseph Daltons Hooker 1849 book, The Rhododendrons of Sikkim-Himalaya with its brilliant illustrations by Walter Hood Fitch.

While the work takes on a particularly European visual aesthetic of its subject, the interest for me is always tied to its present day manifestation – particularly, how the garden has become a public sanctuary for both the unique indigenous flora and fauna of its region, as well as accommodating a significant and evolving collection of the Rhododendron species on the global stage.

My recent doctoral thesis and studio work over the last 15 years has been entirely focussed on the way in which the historical view has shaped a certain aesthetic appreciation for place (through landscape and flora/fauna). I believe that those aesthetics, now several centuries old, continue to draw us back to our appreciation of both the beauty and fragility of nature. Significantly however, I am not proposing a replica of those histories, but rather I am taking an opportunity to highlight the importance of preserving such places in the C21st century context.

The place itself, as natural environment and with its connection to Maori and Pakeha, is multifaceted and therefore always subject to the complexities of current culture and politics. That aside, the here and now is that the creation of this garden (as with many in the Taranaki region) act to educate an audience on the importance and value of preserving and nurturing natural places and ecosystems. Not only do they successfully conserve flora and fauna, but they also act to reinforce the identity of the region. The Taranaki Regional Council has taken on some of these formally privately run gardens ensuring that the legacy of plant and petal continues to attract attention to the region while simultaneously emphasising the importance of conserving our natural resources.

The project aims to significantly acknowledge those visionaries of the past, while bringing to the present the value of the place itself and its commitment to the preservation of native flora and fauna as well as the obvious attraction of creating an environment to grow and display the rhododendron species."

"For nearly two decades my work has been increasingly concerned with the link between early C18th European perceptions of the South Pacific through collection and documentation and present day manifestations of those aesthetics and agendas. For example, how we value nature (flora & fauna) and how that evolves and recedes through the current influence of economy, beauty, politics and ecology.

The story of how nature is initially seen (both in indigenous and European histories) and how it is developed as a 'productive' resource, is always a curious story to tell. Drawn to Pukeiti Rhododendron Gardens, for its inception as a sanctuary, I was particularly inspired by an opening passage in Graeme Smiths Pukeiti book (1997),

“At first glance, the killing fields of Gallipoli and the Somme would appear to have nothing in common with Pukeiti. In a paradox of history, however, one gave birth to the other...

After two world wars and the decimation of many parts of the old World, and not a few areas of

New Zealand, there seemed to be a general coming together of people interested in plants. The ravages of war and its lost generations, combined with the blackened stumps of a blighted local landscape, cleared for pasture, made some people aware of what was being destroyed. Tree, flowers and birds, amongst other things, ‘restoreth the soul’” p 10.

I imagined some of the Pukeiti founders, such as Douglas Cooke who served in Egypt, Gallipoli and France during World War I, returning to New Zealand with the dream of creating a place of natural tranquility and beauty, contrasting completely the devastation of both humanity and landscape experienced through war.

Within the research for this project I have also drawn on some of the C19th plant-hunting stories and the visual representations of those early collections. I was fortunate to see a copy of the precious Joseph Daltons Hooker 1849 book, The Rhododendrons of Sikkim-Himalaya with its brilliant illustrations by Walter Hood Fitch.

While the work takes on a particularly European visual aesthetic of its subject, the interest for me is always tied to its present day manifestation – particularly, how the garden has become a public sanctuary for both the unique indigenous flora and fauna of its region, as well as accommodating a significant and evolving collection of the Rhododendron species on the global stage.

My recent doctoral thesis and studio work over the last 15 years has been entirely focussed on the way in which the historical view has shaped a certain aesthetic appreciation for place (through landscape and flora/fauna). I believe that those aesthetics, now several centuries old, continue to draw us back to our appreciation of both the beauty and fragility of nature. Significantly however, I am not proposing a replica of those histories, but rather I am taking an opportunity to highlight the importance of preserving such places in the C21st century context.

The place itself, as natural environment and with its connection to Maori and Pakeha, is multifaceted and therefore always subject to the complexities of current culture and politics. That aside, the here and now is that the creation of this garden (as with many in the Taranaki region) act to educate an audience on the importance and value of preserving and nurturing natural places and ecosystems. Not only do they successfully conserve flora and fauna, but they also act to reinforce the identity of the region. The Taranaki Regional Council has taken on some of these formally privately run gardens ensuring that the legacy of plant and petal continues to attract attention to the region while simultaneously emphasising the importance of conserving our natural resources.

The project aims to significantly acknowledge those visionaries of the past, while bringing to the present the value of the place itself and its commitment to the preservation of native flora and fauna as well as the obvious attraction of creating an environment to grow and display the rhododendron species."

About the work process:

"I have based several previous projects looking at botanical art techniques and translating that through water based paint and print. Given the vast history of representation surrounding the beautiful rhododendron flower, I am taking a different approach with the final works which will be made in different stages.

The first includes the extensive documentation of the Pukeiti in its different seasons and discussions with people connected with the gardens. Secondly I am undertaking a series of paintings based on my photographs. Rather than purest botanical studies, or referencing a select choice of flower, I am focusing entirely on form. Through this step I aim to present the plant in a way that highlights its particular features, whether it’s the spots on a petal, composite flower structure or leaf.

The final part, and where the two exhibitions separate is in its commercial print form. Here I am experimenting with different print surfaces, filters and light to evoke particular atmospheres around the plant. Very rarely do we choose to go and see the rhododendron plants out of their flowering season, on a rainy day or at dusk. This shift in emphasis also advocates a shift in perception. The value of nature to me is significantly beyond the immediate gratification of a pretty flower. Pukeiti itself represents the very best of our ability to create, nurture and celebrate nature."

June 2018

"I have based several previous projects looking at botanical art techniques and translating that through water based paint and print. Given the vast history of representation surrounding the beautiful rhododendron flower, I am taking a different approach with the final works which will be made in different stages.

The first includes the extensive documentation of the Pukeiti in its different seasons and discussions with people connected with the gardens. Secondly I am undertaking a series of paintings based on my photographs. Rather than purest botanical studies, or referencing a select choice of flower, I am focusing entirely on form. Through this step I aim to present the plant in a way that highlights its particular features, whether it’s the spots on a petal, composite flower structure or leaf.

The final part, and where the two exhibitions separate is in its commercial print form. Here I am experimenting with different print surfaces, filters and light to evoke particular atmospheres around the plant. Very rarely do we choose to go and see the rhododendron plants out of their flowering season, on a rainy day or at dusk. This shift in emphasis also advocates a shift in perception. The value of nature to me is significantly beyond the immediate gratification of a pretty flower. Pukeiti itself represents the very best of our ability to create, nurture and celebrate nature."

June 2018

Image: Detail, Thrown Together by Nicci, Goodin Garden, Okato. Acrylic and chalk on paper. Tabatha Forbes©

The Goodin Project : The gardener, the florist & the artist

Taranaki Garden Festival

November 2017

Working in residence at The Goodin Country Garden, Okato, Taranaki with Nicci Goodin Florist, New Plymouth

"What does having the vision to create a beautiful garden, sharing that place with the public, turning a bunch of flowers into something magical, or painting a plant have in common?

Simply, that the gardener, the florist and the artist share a common passion for plants and a desire to celebrate the delicate beauty that nature inspires.

The collaboration between these three parties was a small opportunity to share a collective passion for place, and for plants that for each has unwittingly become the subject of their life’s work. For Tabatha, it is also a tribute to this family story.

Growing up in the Goodin house hold, Nicci’s environment was one of working in the land (Okato farm) and the families creation of the Goodin Country Garden, which would eventually be shared as a Taranaki Festival destination as well as a lovely place to stay and experience first-hand. Nicci’s subsequent dedication to working with flowers and foliage has taken her all around the world before settling back in New Plymouth as a successful designer florist.

As an artist, Tabatha sees her work as an evolving collection of stories from the South Pacific, linked to the early European history of botanical representation discussed within a contemporary rhetoric."

During this project Tabatha spent time painting one of Nicci's creations from the garden, in residence at the Goodin homestead during the Garden Festival.

www.niccigoodin.co.nz

www.goodincountrygarden.co.nz

Taranaki Garden Festival

November 2017

Working in residence at The Goodin Country Garden, Okato, Taranaki with Nicci Goodin Florist, New Plymouth

"What does having the vision to create a beautiful garden, sharing that place with the public, turning a bunch of flowers into something magical, or painting a plant have in common?

Simply, that the gardener, the florist and the artist share a common passion for plants and a desire to celebrate the delicate beauty that nature inspires.

The collaboration between these three parties was a small opportunity to share a collective passion for place, and for plants that for each has unwittingly become the subject of their life’s work. For Tabatha, it is also a tribute to this family story.

Growing up in the Goodin house hold, Nicci’s environment was one of working in the land (Okato farm) and the families creation of the Goodin Country Garden, which would eventually be shared as a Taranaki Festival destination as well as a lovely place to stay and experience first-hand. Nicci’s subsequent dedication to working with flowers and foliage has taken her all around the world before settling back in New Plymouth as a successful designer florist.

As an artist, Tabatha sees her work as an evolving collection of stories from the South Pacific, linked to the early European history of botanical representation discussed within a contemporary rhetoric."

During this project Tabatha spent time painting one of Nicci's creations from the garden, in residence at the Goodin homestead during the Garden Festival.

www.niccigoodin.co.nz

www.goodincountrygarden.co.nz

|

Image:The Goodin Country Garden, Okato and two of Nicci's bouquets from the garden. T.Forbes ©

|